Commentary on Remuseum Research Report: Museum Missions and Transparency

Stephen Reily, Founding Director, Remuseum

The people leading American art museums into the future – directors, staff leaders, trustees, and funders – are facing a number of great challenges, all at the same time: rapidly rising costs, reduced visitation, increased competition, and broadened ambitions and public expectations. It is a period of profound change, and managing change requires not just new skills, but more information, than ever before.

When I became a museum director myself in 2017, however, I found that such information was hard to find.

Remuseum’s initial research, issued today, reveals that individual museums share little data about their own operations and that the researchers who do gather museum data either agree to keep it private or report it only on an aggregated basis. As far as I know, no research project has tried to encourage the sharing of actual museum data with both the field and the public. Until now.

More transparency will be good for the public and it will be good for museums.

It will be good for the public because museums are public institutions. The Financial Accounting Standards Board created a special accounting rule for museums allowing them to keep artwork off their balance sheet because they hold it for “the public trust.” They benefit from tax subsidies (deductions related to contributions of liquid assets and art) and exemption for taxes on an enormous scale. Many get substantial operating funds from their municipalities and states. Everything from their 501c3 nonprofit status to the Code of Ethics of the Association of Art Museum Directors emphasizes that the underlying purpose of art museums is to serve the public (not their donors) with art and education. The public that does so much to fund museums have a right to know more about institutions that claim to serve the public above all.

Sharing data will be good for museums as well. More information about other museums will help individual museums (including their boards and funders) better evaluate their operations and decide how they can best fulfill their own missions. It will also help museums innovate by giving outsiders tools to understand the field better and to generate ideas and opportunities to help the field thrive.

Remuseum’s report highlights a lack of transparency by many museums but it also highlights the museums that do share specific data with the public – and invites others to follow their example. It also begs the question: why have art museums shared so little information?

I believe there are two answers.

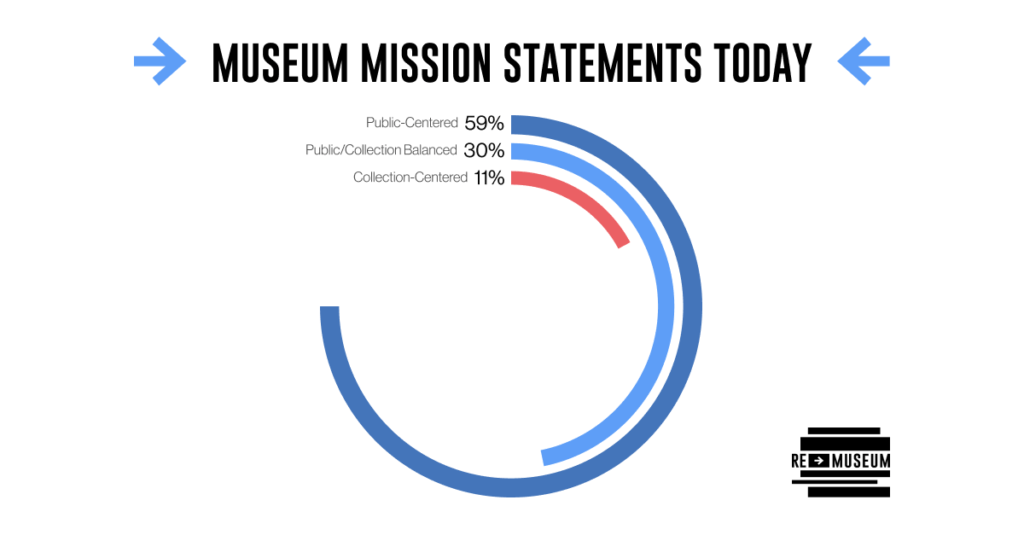

The first lies in the radical nature of the change that museums are managing, one that is also documented in Remuseum’s report: the transition from missions centered on objects to missions centered on the public. It represents one of the most radical shifts in any industry (cultural, nonprofit, or for profit) that I have seen in my lifetime.

Change management is hard, and legacy missions retain a strong hold on museum practices, including approaches to sharing information. Under old missions, the field’s value lay in developing expertise shared (on its own terms) with the public; it would not be surprising that the field’s approach to sharing information might also follow that approach, sharing data only on a need-to-know basis. Separately, to the extent that old missions reflected the interests of traditional museum funders, an approach to sharing information that focuses predominantly on buildings, acquisitions, and exhibitions (and the donors who fund them) may explain why the information that museums do share seems to relate more to the object-focused past than the public-focused present.

The second reason lies in the challenges that museums face in managing so much change. My own experience as a museum director taught me first-hand how hard it is to run these unsustainable enterprises, especially when their long-held practices add expenses without corresponding revenue. Whether from their ever-growing buildings; ever-growing collections; ever-rising standards of care and costs of storage; the desire and call to offer more equitable wages and benefits to its workers; earned-income lines of business that may lose more money than they generate; and increasingly expensive exhibitions, museums continually add expenses that outpace their revenues, which itself calls out the tension between old missions and new. Only the dramatic increase in personal wealth that has supported an increase in contributed revenue (and a booming market that has buoyed the value of endowments) have allowed museums even to keep close.

Pandemic-era relief represented the greatest period of federal funding in the arts ever. For most institutions, that cash has been spent. At the same time, compensation costs are rising; visitor numbers remain below pre-pandemic levels; and museum trustees and donors remain singularly excited about building ever-larger buildings and ever-larger collections, which only make operations more expensive. Well-documented dissatisfaction with museum work makes not just financial sustainability but worker sustainability a key concern for managers. And even when museums do attract more visitors and manage to balance their budgets, they face a media climate that reports on the progressive critique of museums for not changing fast enough as if it were the same thing as the more conservative critique from those who wish museums had never changed at all.

While museum leaders know these realities, they have not been encouraged to share them. And no museum wants to look weaker than its peers. I appreciate these feelings. But almost every other public field has overcome such fears without major repercussions, and often with benefits.

For museums to succeed at their public-facing missions; for museums to benefit from the ideas of people outside the field; for museums to generate the kind of trust that new generations of donors will require to justify their support; and for museums to find new solutions that balance the need to preserve and study objects with the need to engage and serve a growing public (one more obsessed with visual imagery than ever), they will need to open their books and share at least a few critical data points with the public. I hope they will agree.